Indecent proposals

The pressure to provide evidence, the fear of fighting a superior, the probable impact on career, and adverse publicity prevent women from reporting sexual harassment

In the mid-90s, an incident shook the Pakistani corporate world. Ayesha*, a female employee in a multinational pharmaceutical company complained of sexual harassment by her male superior. His inappropriate conduct wasn’t limited to her alone; many women from the organisation had dodged his advances and had adopted the ‘suffer-in-silence’ approach. Ayesha wasn’t going to be one of them. She stepped up and issued a verbal complaint to the management. And then all hell broke loose.

The management asked her, point blank, to take back her complaint since the culprit was a very senior member of the organisation and a ‘family man with grown up daughters.’ She refused. The harasser, in the company of another colleague, admitted to what he had done and told her to take back her complaint or suffer the consequences. Instead, she registered a written complaint and also contacted the regional management, who told her that they had full faith that the Pakistan office would handle her case fairly.

An inquiry committee had to be formed. The standard practice of inducting a female member was ignored, thus bringing into question the integrity of the committee. In an online statement to an advocacy group for civil liberties, she related, “The inquiry committee, instead of playing the role of an unbiased body, followed the lead of the management and formalised the intimidation process. In this instance it led to defamatory remarks, threats and ridicule by the higher management to coerce me to take back the complaint. The management threatened me and labelled me a ‘troublemaker’ and ‘whistleblower’.”

The list of witnesses she had issued to the management were individually tracked down one by one. Using both intimidation and reward tactics, the committee told those witnesses to withdraw their written statements regarding having suffered similar treatment by the culprit. One of the witnesses, who had taken a transfer from the culprit’s department because of his harassment towards her, even came out in support of him. Needless to say, the witnesses who changed their stance were all given promotions and sent on foreign trips once the investigation concluded.

Ayesha was forced to work under her harasser whose behaviour went from bad to worse — especially now since he realised that he could get away with murder in broad daylight. When she complained again, she was told to put up with it or leave. She chose the latter.

It was only 14 years later that the government of Pakistan would introduce a law criminalising workplace sexual harassment.

Safe on paper

On Jan 30, 2010 the Bill against Harassment of Women at the Workplace was signed into law by then president, Asif Ali Zardari. During its passage there had been strong criticism from religious parties, and last-minute amendments also extended the protection to men as a compromise.

But even four years later, many remain ignorant of its existence. However, with an increasing number of women joining the workforce in the corporate sector, many organisations have chosen to adopt their own Standard Operating Procedures when it comes to the handling of a complaint regarding sexual harassment in the workplace. Having said that, these organisations often don’t make it a point to make their employees aware of the existence of such policies. As a result, these questions are left unanswered: What is the procedure to file complaints, how are they to be handled and what are the repercussions for harassing another colleague?

Bullying by numbers

It isn’t just men who may engage in inappropriate and intimidating conduct, and sometimes both male and female colleagues will gang up against the victim of harassment.

“We once hired a woman, a fresh graduate, very bright and one of the best in that department,” related Hasan who has been working at a top managerial position in a media-buying house for several years now. “She used to wear sleeveless outfits and a group consisting of several female and male colleagues began giving her lectures on morality.”

She immediately went and complained to her boss. “I didn’t take it seriously at first,” said Hasan, “I thought it was a passing phase. She wasn’t attracting any kind of vulgar attention and what she wore was her personal business anyway. But the second time when she complained, she broke down crying in my office. That’s when I knew things had gotten serious.”

The harassment by her colleagues, instead of dying down, had only become worse. It came to a point where she was having difficulty doing her work. “We filed a complaint with the HR and, as per policy, a woman manager was inducted into the investigating team,” said Hasan, “Eventually that group was made to apologise to her.”

Unspoken policy: no woman, no cry

Ask a group of people employed in the corporate sector in which industry they believe women enjoy the same treatment as their male colleagues at work, or where the chances of them being sexually harassed are at a minimum, and the most common response you get is banking or advertising.

While the participation of women is very prominent in both of these sectors, it emerges there are a few banks and advertising agencies that have an ‘unspoken policy’ of not hiring women at all! Some go as far as to restrict their male employees from even receiving any female guests.

When asked why, responses ranged from claims that women are unable to spend as many hours at work as compared to men or that women are a ‘distraction’ to their male colleagues and ruin the ‘environment’ at the office. Finally what also emerges is an institutional unwillingness to deal with potential sexual harassment complaints.

“While visiting a friend’s advertising agency, it took me a while to figure out what was odd about the place,” said Asad, who also works in advertising. “I realised there was not a single woman … anywhere!” says a surprised Asad. “This was rather strange, because you expect to find women in such a workplace, if for nothing else then to contribute to the women’s product market at least. When I asked my friend he laughed and said they’ve had issues before, where employees have gotten ‘involved’ and things have gotten ‘ugly’ so now to prevent that they simply don’t hire women.”

According to them, prevention is better than cure. If there are no women, there is going to be no sexual harassment. Academic studies in the subject, however, show that segregation fuels sexual harassment instead of diminishing it. Adopting a policy based on avoidance is not a solution.

Fatal attraction: when the roles are reversed

“I came across a very strange case once,” related Fahad*, who works in local bank. “An acquaintance worked in the head office of a bank and soon after he joined, he became the object of the somewhat indecent attention of his female boss.” He did not return her affectation and that became a source of problem at work. From harmless flirting, the boss’s behaviour slowly started to become aggressive.

“He would be called into her office at the smallest of pretexts and plied with questions about his personal life, asked out for dinner (which he’d politely refuse) and his interaction with other female colleagues was closely monitored,” said Fahad, “He was even told by his boss that she didn’t approve of him interacting with them! Every time she made a pass at him and he wouldn’t respond, she would find an excuse to berate him in front of his other colleagues. He didn’t know what to do!”

Needless to say the man was mortified. Going to his colleagues and complaining would only invite teasing from their side. After all, what kind of a man doesn’t want attention from another woman? Most importantly, ‘real’ men don’t get bullied by women. Eventually, he decided to quit and find employment in another organisation.

The general assumption might be that only women are harassed, but the opposite can also hold true. Where most women don’t register complaints for fear of having their reputations ruined by defamatory remarks, the stigma surrounding men being harassed by women very much exists and is a cause of great mental and emotional stress by the victims. Men often ask themselves the same questions women do in a similar situation: “Whom do I go to? Who will believe me? Will this blow up in my own face instead?”

*Names of all of the people mentioned in the article have been changed to protect privacy

Newspaper view: [Click for larger image]

Media ethics: Questionable conduct

Muhammad Sikandar stands next to his wife during a standoff with police in Islamabad on August 15, 2013. — Photo by AFP

The media’s own code of conduct floundered and Pemra oversight is simply not viable. Who will then watch the watchmen?

“I’d say it was a failure at both fronts — at the media’s end and a larger one at the government’s side. It was a big story, everyone was going to cover it, but it needed to be done with certain rules in mind,” said Fahad Hussain, a noted columnist and electronic media professional.

The story he mentions unfolded on August 15, 2013, when a heavily armed Mohammad Sikandar held the Blue Area of Islamabad hostage for over six hours while he demanded the imposition of Sharia Law in Pakistan. Glued to their television screens, the citizens of Pakistan watched the entire drama unfold live on the many news channels that were broadcasting it. Sikandar got the attention he so badly wanted, along with live interviews; he is now a household name.

Reporting on a conflict situation, especially one that involves hostages and rescue operations, is an extremely sensitive and risky affair. And in the case of Sikandar, a lot of basic rules of journalism were broken — formal and informal rules and indeed, rules the media had set for itself once upon a time.

Rule: No live interview of any hostage taker.

Broken: Sikandar interacted with television media crew on location and his demands were broadcast.

Rule: Troop movement and deployment should not be shown and locations should not be given up as it can endanger the lives of hostages.

Broken: Sikandar’s movements were tracked in both close and long shots, security forces cordoning the area and closing on to him were shown.

Rule: Always assume that the hostage taker has access to your reporting.

Broken: Sikandar’s wife was constantly seen talking on her phone. The person on the other end could have been updating her on the aspects of the event being broadcast on TV that they weren’t privy to.

“When there is a total blackout of information, the media will do anything to get whatever information it can,” said Hussain, stressing on the importance of having an official spokesperson from the government or the security forces’ side. “It helps you draw parameters, you get real-time hard information.

The government should have Standard Operating Procedures in place so that whenever breaking news or a developing story happens, they can relate information in a timely manner.”

“Did they learn anything from it?” he continued, “No. Would the coverage be the same in the case of another similar incident? Yes. Are the government and media better off this way? Absolutely not.”

The rules mentioned above stem from a code of conduct developed by the media itself, in response to another, far deadlier incident: the attack on the GHQ in Rawalpindi in 2009, where, in some cases, troop deployment details and other sensitive information was telecast. Eventually, the government imposed a media blackout on two major television news networks, albeit briefly.

It was time for the media to introspect as to where they were going wrong.

Subsequently, a meeting of the directors of various channels, editors of newspapers and journalists took place in Karachi and Islamabad. “It was basically the result of watching us cover terrorism day in and day out in 2008-09. It was reaching a point where we (all of the news channels) were just getting hysterical,” said Hussain who initiated the move. “It was born out of an informal discussion I was having with some other colleagues, who are heading other channels. We thought: ‘why not get together and talk about what we can do’. From there it became a little more serious.”

Collectively, they chartered what would later be referred to as the “Code of conduct for media broadcasters or cable TV operators”. These were rules that the channels would follow regarding the coverage of conflict, hostage situations and the depiction of violence on TV. “I believe the various news directors came up with 15-16 points,” said Mazhar Abbas former Secretary General of the Pakistan Federal Union of Journalists, “There was also a delay system (between reporting and going live) which some channels follow to this day. Even if someone violated a rule, there and then, colleagues from other channels would contact them and remind them of the rules.”

The system stayed in place for a few months. And like most good things in Pakistan, it eventually fell apart. “The idea was good but the support of media owners wasn’t there,” said Abbas, “The position that an editor enjoys in a newspaper is what the position of the director news should be in a TV channel. Ultimately it’s the pressure from the management that influences the news. The power of the editor is decreasing.” News channel owners are essentially taking over the role of editors themselves.

So if the media failed to follow the rules that it set for itself, does that mean that a government clampdown is inevitable? “That can only happen when you push people to a point where they say they’ve had enough,” responded Hussain, “I do agree that if we don’t halt the slide we’ll lose the people we are catering to — our viewers.”

Given Pakistan’s history with state censorship, the idea of government control over broadcast and print is unpalatable. “Regulations have always been misused by the government,” argues Abbas. “Whether in the form of press censorship or advisors, the advisors adopt a ‘different’ method … that is how corruption in the media started. The government started bribing media using advertisements. That’s why nowadays you don’t see many stories against the government. It’s a Rs50-60billion market and everyone wants access to it. In that race, independence of the media has been compromised in many cases. Media channels in Pakistan are private, but certainly not independent.”

What about the official government regulatory body already in place? “Pemra has lost its credibility as an independent body,” responded Abbas, “It never has been one. From its chairman to its members, everyone is nominated by the president. It has failed to execute any of its own laws.” What then is the solution?

“Setting up an independent ombudsman would be a better option to issue notices or take complaints. You have to have some kind of a forum, which is not available in the electronic media. It would work even if the government implements Pemra laws, but with an amendment that the chairman Pemra is appointed by the parliament and not by the president. Make him accountable to the parliament,” he stressed.

Setting up an independent body with the contribution and consensus of news directors, editors and journalists is one of the more ‘practical solutions’, according to Hussain. “But where does that initiative come from?” he questioned, “The government, Pemra, Ministry of Information, etc. have to go beyond their own, and that’s easier said than done.” And this is where the choice of regulator becomes crucial

“It is very difficult for a person who has never dealt with the newsroom, to come up with an implementable code of conduct,” he stated, “Which is why ours worked for as long as it did — it was a product of people who are familiar with the nuts and bolts of the newsroom functions. If we are to have a workable code of conduct it has to be born out of people in the newsroom.”

Newspaper view: [Click for larger image]

Destination: Pakistan

“Adios Iran, Hola Pakistan” This was the update on Spanish cyclist Javier Colorado Soriana’s Facebook page on January 20th, right after he crossed the Iran-Pakistan border into Balochistan. Pakistan only heard of him after an attack took place on his levies escort, killing six of the guards who were escorting him through Mastung. As the initial blame was placed squarely on Soriana’s shoulders, many wondered what would possess a foreigner to rush in where even locals fear to tread. Well, the story’s been through some changes since then, and may not be as open and shut as initial reports claimed. Kidnappings, killings and chaos … it’s a wonder that Western tourists still pluck up the courage to visit Pakistan — and in fact travel through some of the most dangerous areas of this country. But they do, often armed only with decades-old guidebooks. Some are naïve, others passionate and determined, and some actually enjoy the thrill of journeying through what Newsweek infamously called “The most dangerous nation in the world”. Here, we look at the experiences; some good, some bad and some life-threatening, that foreign tourists have had in Pakistan.

Put everything else on hold. Pack your bags and go see the world. You’ll find a couch to surf on everywhere you go.

“Hello, is that Madeeha?”

“Yeah.”

“I’m at the railway station.”

“Who? What?!” I thought to myself. It was 8am, on a Sunday. I struggled to find my bearings and a reply.

And then it hit me: CouchSurfing Ambassador Ciro Rendes was to arrive in Karachi that morning. Paranoia kicked in.

“Where are you standing?”

“Near the main entrance.”

“Stay there, I’ll be there in 10 minutes.”

Rendes, originally from Lisbon, Portugal, is part of the CourchSurfing network of passionate travellers that seeks to build meaningful connections between globetrotters and local hosts. In its essence, CouchSurfing allows travellers to take a trip abroad on a budget, and experience authentic colours and flavours of the people they encounter on their journeys. Guests and hosts meet online, at the CouchSurfing portal. As a guest, you have to be on your best behaviour and as a host you have to make sure your guest is comfortable. Rendes was arriving to taste a slice of Pakistan; he was to stay with me.

My guest did not speak a word of Urdu, of course, nor was he carrying a mobile phone with a functioning Pakistani number. I was concerned for his safety, and rushed to the Cantt Railway Station.

But at the station, Rendes was nowhere to be found. I looked everywhere for him — inside the gates of the station, at the various teahouses and hotels to see if I could spot him sitting there, and I saw nothing. Afraid of asking people around me lest that bring too much attention to the fact that there was a foreigner lurking around, I eventually decided to call the last number I had spoken to him on.

At the office of the payphone service, I asked a smiling young man if a person who didn’t look like he was from “around here” had dropped by. The man excitedly responded, “You mean the boy with the really big bag?!” opening his arms wide to show exactly how ‘big’.

I couldn’t help but feel amused; backpackers, and the baggage they carry, aren’t a regular sight here. He told me that my guest was sitting next to the model train inside the station. Sure enough, I found Rendes there. On our way to the car, I noticed that most of the people in the area were smiling at us — they had known of his presence all along!

But Rendes was safe. He went to sleep on my ‘couch.’

***

Gizem*, a high-strung 47-year-old Turkish math teacher-turned-backpacker, was already in Karachi when I was introduced to her. She had travelled overland all the way from Antalya, Turkey to Karachi, Pakistan and planned to head to Lahore and subsequently to India. Barely fluent in English, communicating with Gizem involved a spontaneous potpourri of several languages as well as a lot of hand gestures and actions.

But Gizem was terribly clueless about the lands that she was traversing: having travelled from Zahedan, Iran to Quetta, Pakistan on a bus, she did not understand why Iranian authorities chose to delay the bus by three days, why there was a perpetual sense of foreboding in the air while travelling through the province, or why her hosts in Quetta asked her to stay mostly indoors.

All of that made sense when Gizem woke up the first morning on my couch. Adamant that she would travel by herself and refusing any help whatsoever, Gizem came up to me with a dingy old, yellowed guidebook in her hands. “No one seems to know where the Presidential Palace is!” she announced with great frustration, as she showed me a chapter of her travel guide titled ‘Sights to See in Karachi’.

Presidential Palace?

I took the book from her and saw that it had been published in the 1960s. And then I calmly told her that in 1969 the capital of Pakistan had been shifted from Karachi to Islamabad, and in 1970 the federal government had moved there. At that moment, it dawned upon me that Gizem was travelling through The Hippie Trail of the 1970s!

And yet, Gizem was one strong woman. During her stay in Karachi, she beat up a taxi driver for attempting to molest her, took a rickshaw all the way to Hawks Bay and even bought her own ticket to Lahore from the railway station.

Of course, she always had a couch to surf on in Karachi. She was always welcome at my house.

***

The most apt description of Way C., a Brazilian of Taiwanese descent, is that of a “trouble magnet.” Everywhere he went in Karachi, he was greeted by danger — Way C. had arrived in Karachi with hopes of having an “exciting time”, and that is precisely what he got.

We were en route to some salt works, driving merrily on Mauripur Road, when out of the blue, a group of women descended on the cars on the roads, slapping them and asking drivers to move out of the way. Within minutes, an entire neighbourhood from Lyari was out on the main road, with men, women and children carrying whatever they could and running for it.

Turns out, there was an operation taking place in that particular neighbourhood. Between the law enforcement agencies and the people they were after, common citizens did not feel safe. We managed to find a way through the fisheries and drove straight out into Clifton, where we stopped to catch our breaths, have some juice and process what just happened.

By the time Way C. went to sleep, he had already jotted down his exciting experience of the day. By the time he’d leave Karachi, he had many more entries to make in his journal. CouchSurfing had introduced him to the “real” Pakistan.

A state of siege

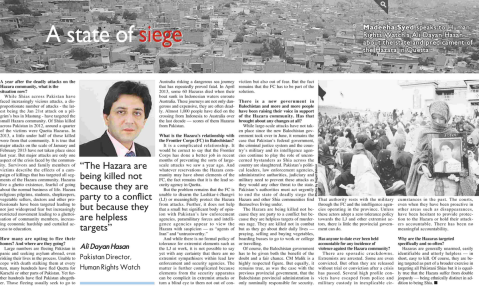

Madeeha Syed speaks to Human Rights Watch’s Ali Dayan Hasan about the state and predicament of the Hazara in Quetta

A year after the deadly attacks on the Hazara community, what is the situation now?

While Shias across Pakistan have faced increasingly vicious attacks, a disproportionate number of attacks – the latest being the Jan 21st attack on a pilgrim’s bus in Mastung – have targeted the small Hazara community. Of Shias killed across Pakistan in 2012, around a quarter of the victims were Quetta Hazaras. In 2013, a little under half of those killed were from that community. It is true that major attacks on the scale of January and February 2013 have not taken place since last year. But major attacks are only one aspect of the crisis faced by the community. Survivors and family members of victims describe the effects of a campaign of killings that has targeted all segments of the Hazara community. Hazaras live a ghetto existence, fearful of going about the normal business of life. Hazara religious pilgrims, students, shopkeepers, vegetable sellers, doctors and other professionals have been targeted leading to not just widespread fear but increasingly restricted movement leading to a ghettoisation of community members, increasing economic hardship and curtailed access to education.

How many are opting to flee their homes? And where are they going?

Large numbers are fleeing Pakistan in panic and seeking asylum abroad, even risking their lives in the process. Unable to cope with death stalking them at every turn, many hundreds have fled Quetta for Karachi or other parts of Pakistan. Yet further hundreds have fled Pakistan altogether. Those fleeing usually seek to go to Australia risking a dangerous sea journey that has repeatedly proved fatal. In April 2013, some 60 Hazaras died when their boat sunk in Indonesian waters enroute Australia. These journeys are not only dangerous and expensive, they are often deadly. Almost 1,000 people have died on the crossing from Indonesia to Australia over the last decade — scores of them Hazaras from Pakistan.

What is the Hazara’s relationship with the Frontier Corps (FC) in Balochistan?

It is a complicated relationship. It would be correct to say that the Frontier Corps has done a better job in recent months of preventing the sorts of large-scale attacks we saw a year ago. And whatever reservations the Hazara community may have about elements of the FC, the fact remains that it is the lead security agency in Quetta.

But the problem remains that the FC is unable to disarm the Lashkar-i-Jhangvi (LJ) or meaningfully protect the Hazara from attacks. Further, it does not help that a small but significant body of opinion with Pakistan’s law enforcement agencies, paramilitary forces and intelligence agencies appear to view the Hazara with suspicion — as “agents of Iran” and “untrustworthy.”

And while there is no formal policy of tolerance for extremist elements such as the LJ at work, it is not possible to say yet with any certainty that there are no extremist sympathisers within lead law enforcement and security agencies. The matter is further complicated because elements from the security apparatus can be complicit in extremist attacks or turn a blind eye to them not out of conviction but also out of fear. But the fact remains that the FC has to be part of the solution.

There is a new government in Balochistan and more and more people have been raising their voice in support of the Hazara community. Has that brought about any changes at all?

While large-scale attacks have not taken place since the new Balochistan government took over in June, it remains the case that Pakistan’s federal government, the criminal justice system and the country’s military and its intelligence agencies continue to play the role of unconcerned bystanders as Shia across the country are slaughtered. Pakistan’s political leaders, law enforcement agencies, administrative authorities, judiciary and military need to prevent these attacks as they would any other threat to the state. Pakistan’s authorities must act urgently to end the state of deadly siege the Hazara and other Shia communities find themselves living under.

The Hazara are being killed not because they are party to a conflict but because they are helpless targets of murderous rage. They are killed not in combat but as they go about their daily lives — praying, selling and buying vegetables, boarding busses to go to work or college or travelling.

Of course, the Balochistan government has to be given both the benefit of the doubt and a fair chance. CM Malik is a highly respected figure. But equally, it remains true, as was the case with the previous provincial government, that the Balochistan provincial administration is only nominally responsible for security. That authority rests with the military through the FC and the intelligence agencies operating in the province. Unless these actors adopt a zero tolerance policy towards the LJ and other extremist actors, there is little the provincial government can do.

Has anyone to date ever been held accountable for any incidence of violence against the Hazara community?

There are sporadic crackdowns. Extremists are arrested. Some are even convicted. But often they are released without trial or conviction after a crisis has passed. Several high profile convicts have escaped from police and military custody in inexplicable circumstances in the past. The courts, even when they have been proactive in other areas such as disappearances, have been hesitant to provide protection to the Hazara or hold their attackers accountable. There has been no meaningful accountability.

Why are the Hazaras targeted specifically and so often?

Hazaras are generally unarmed, easily identifiable and utterly helpless — in short, easy to kill. Of course, they are being targeted as part of a broader exercise in targeting all Pakistani Shias but it is equally true that the Hazara suffer from double jeopardy — being ethnically distinct in addition to being Shia.

Newspaper view: [Click for larger image]

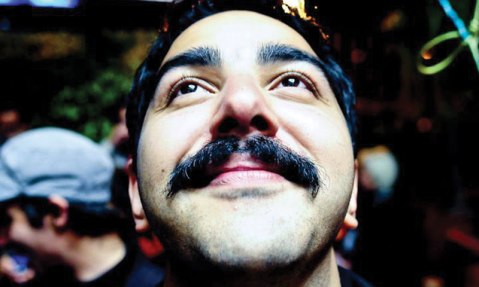

Mad about the mooch

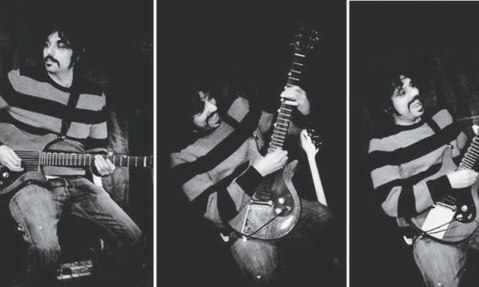

There must be some truth to the saying ‘agar mooch nahin to kuch nahin’. After all, that epitome of manliness in this country, Maula Jatt, has one. But how popular is the mooch in contemporary Pakistani culture? We asked a musician, a filmmaker and an aam admi on their views on their real and non-existant whiskers

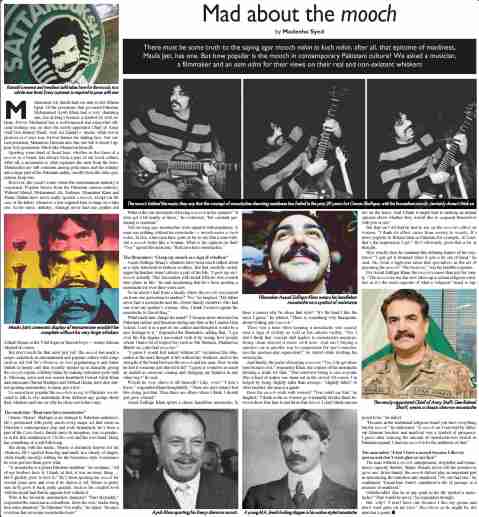

The mooch behind the music: they say that the concept of moustaches denoting manliness has faded in the past 20 years but Omran Shafique, with his horseshoe mooch, certainly doesn’t think so.

Mohammad Ali Jinnah had one and so did Allama Iqbal. Of the presidents that governed Pakistan, Mohammad Ayub Khan had a very charming one, Zia-ul-Haq’s became a symbol of, well, infamy. Pervez Musharraf has a well-trimmed and somewhat efficient looking one, as does the newly-appointed Chief of Army Staff Gen Raheel Sharif. Asif Ali Zardari’s ’stache, while not as glorious as it once was, forever frames his smiling face. Our current president, Mamnoon Hussain also has one but it doesn’t appear very prominent. Much like Mamnoon himself.

Sporting some kind of facial hair, whether in the form of a mooch or a beard, has always been a part of our local culture. After all, a moustache is what separates the men from the boys. Moustaches are still common among policemen and the military and a large part of the Pakistani public, mostly from the older generation, keep one.

However, this wasn’t a rule where the entertainment industry is concerned. Popular heroes from the Pakistani cinema industry, Waheed Murad, Mohammad Ali, Nadeem, Moammar Rana and Shaan Shahid have never really sported a mooch, except (in the case of the latter) whenever a role required him to strap on a fake one. In the music industry, Alamgir never had one, neither did Zohaib Hasan or the Vital Signs or Junoon boys — minus Salman Ahmed of course.

But don’t reach for that razor just yet! The mooch has made a major comeback in entertainment and popular culture with songs such as Ali Gul Pir’s Waderai ka beta popularising it and Sattar Buksh (a trendy café that recently opened up in Karachi) giving the mooch a quasi-celebrity status by making customers pose with it. Musician, actor and our current heartthrob Fawad Afzal Khan and musicians Omran Shafique and Mekaal Hasan, have also started sporting moustaches, to name just a few.

To assess how popular the mooch is in aaj ka Pakistan, we decided to talk to two individuals from different age groups about their whiskers and one on why he chose not to have any.

The musician: “Real men have moustaches”

Omran ‘Momo’ Shafique is no stranger to Pakistani audiences. He’s performed with pretty much every major act that exists in Pakistan’s contemporary pop and rock firmament, he’s been a part of the Coke Studio family since its inception, was co-producer in the first instalment of Uth Records and his own band, Mauj, has something of a cult following.

But along with his music, Momo is definitely known for his whiskers. He’s sported them big and small, in a variety of shapes, while finally (mostly) settling for the horseshoe style. Sometimes he even just lets them grow wild.

“A moustache is a proud Pakistani tradition,” he exclaims. “All of my brothers have it. I think, at first, it was an ironic thing … but I quickly grew to love it.” He’s been sporting his mooch for several years now and even if he shaves it off, Momo is pretty sure he’ll grow it back pretty quickly. Such is his comfort level with his facial hair that he appears lost without it.

Who is his favourite moustached character? “Burt Reynolds,” responded the musician in a heartbeat. Does his own ‘stache bring him extra attention? “In Pakistan? Not really,” he stated, “because everyone has awesome moustaches here.”

What is the one downside of having a mooch in his opinion? “It does get a bit unruly at times,” he confessed, “but constant gardening is essential.”

Not too long ago, moustaches were equated with manliness. A man was nothing without his moustache — mooch nahin to kuch nahin. In fact, some men have gone as far to say that a man without a mooch looks like a woman. What is his opinion on that? “Yes,” agreed the musician, “Real men have moustaches.”

The filmmaker: “I keep my mooch as a sign of rebellion”

Assad Zulfiqar Khan’s whiskers have been much talked about as a style statement in fashion weeklies. But that carefully curled, upper lip hairline wasn’t always a part of his life. “I grew up anti-mooch actually. This fascination with facial follicles was a much later phase in life,” he said mentioning that he’s been sporting a moustache for over three years now.

So he doesn’t hail from a family where the mooch was passed on from one generation to another? “No,” he laughed, “My father never had a moustache and the closest family members who had one were my mother’s cousins. Also, I think I used to equate the moustache to Zia-ul-Haq.”

What made him change his mind? “I became more interested in Pakistani culture and literature during my stint at the London Film School. I saw it as a part of our culture and thought it would be a nice homage to it,” responded the filmmaker, adding that, “I got over the Zia stigma I associated with it by seeing how people whom I had a lot of respect for (such as Mir Murtaza, Shahnawaz Bhutto etc.) also had mooches.”

“I guess I would feel naked without it!” exclaimed the filmmaker at the mere thought of life without his whiskers, such is the strength of the bond between the mooch and the man. How would he feel if someone just shaved it off? “I guess it would be as much an assault as someone coming and changing my features in any other way!” he said.

Would he ever shave it off himself? Like, ever? “I don’t know,” responded Khan thoughtfully, “There are days when I feel like doing just that. Then there are others when I think I should just grow a beard.”

Assad Zulfiqar Khan sports a classic handlebar moustache. Is there a reason why he chose that style? “It’s the kind I like the most I guess,” he related, “There is something very therapeutic about twirling one’s mooch.”

There was a time when keeping a moustache was considered a sign of civility as well as his (ahem) virility. “No, I don’t think that concept still applies to moustaches anymore. Being clean shaved is more civil now. And isn’t buying a massive car or gun the way to compensate for one’s insecurities the modern-day equivalent?” he stated while twirling his moustache.

And finally, the perks of keeping a mooch; “Yes, I do get attention because of it,” responded Khan, the corners of his moustache forming a smile for him, “This interview being a case in point. Plus it kind of makes one stand out in the crowd. Of course, I’m helped by being slightly taller than average.” Slightly taller? At 6feet 6inches, the man is a giant!

Does the mooch work with women? “You could say that,” he laughed, “I think as far as women go it instantly divides them between those that hate it and those that love it. I don’t think anyone sits on the fence. And I think it might lead to making an instant opinion about whether they would like to acquaint themselves with you or not.”

But that isn’t all that he had to say on the mooch’s effect on women, “I think its effect varies from society to society. It’s more popular in Britain than in Pakistan for example. At least, that’s the impression I get.” He’s obviously given this a lot of thought.

How exactly does he maintain this defining feature of his existence? “I just get it trimmed when it gets a bit out of hand,” he said. Ah, from a high-end salon that specialises in the art of grooming the mooch? “The local nai,” was his humble response.

For Assad Zulfiqar Khan, the mooch is more than just for vanity. “The mooch for me has now taken up a certain religious rebellion as it’s the exact opposite of what a ‘religious’ beard is supposed to be,” he stated.

“Because in the traditional religious beard you have everything but the mooch,” he elaborated, “A mooch (as I was told by different Islamiat teachers and maulvis) was a symbol of arrogance.

I guess after noticing the amount of moustache-less beards in Pakistan expand, I find my mooch to be the antithesis of that.”

The aam admi: “I don’t have a mooch because I like my qorma and don’t want ghee on my face”

The man without a mooch, entrepreneur, storyteller and (sometimes) capacity builder, Shakir Husain, never felt the pressure to grow one. In his family, the mooch did not play an important part in announcing the transition into manhood. “No one had one,” he confirmed, “Facial hair wasn’t considered a rite of passage or a measure of manhood.”

Unbelievable! Has he at any point in his life sported a moustache? “That would be never,” he responded strongly.

But, why? “I don’t have one because I like my qorma and don’t want ghee on my face.” Moochless as he might be, the man has a point.

Newspaper view: [Click for larger image]

Small soliders

If you have time to spare, there isn’t a better way to spend it than making a sick child’s day a little brighter.

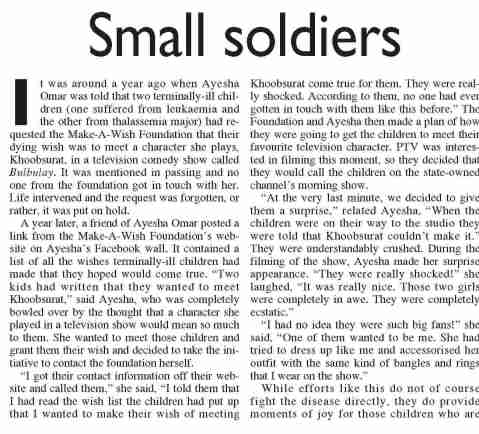

It was around a year ago when Ayesha Omar was told that two terminally-ill children (one suffered from leukaemia and the other from thalassemia major) had requested the Make-A-Wish Foundation that their dying wish was to meet a character she plays, Khoobsurat, in a television comedy show called Bulbulay. It was mentioned in passing and no one from the foundation got in touch with her. Life intervened and the request was forgotten, or rather, it was put on hold.

A year later, a friend of Ayesha Omar posted a link from the Make-A-Wish Foundation’s website on Ayesha’s Facebook wall. It contained a list of all the wishes terminally-ill children had made that they hoped would come true. “Two kids had written that they wanted to meet Khoobsurat,” said Ayesha, who was completely bowled over by the thought that a character she played in a television show would mean so much to them. She wanted to meet those children and grant them their wish and decided to take the initiative to contact the foundation herself.

“I got their contact information off their website and called them,” she said, “I told them that I had read the wish list the children had put up that I wanted to make their wish of meeting Khoobsurat come true for them. They were really shocked. According to them, no one had ever gotten in touch with them like this before.” The Foundation and Ayesha then made a plan of how they were going to get the children to meet their favourite television character. PTV was interested in filming this moment, so they decided that they would call the children on the state-owned channel’s morning show.

“At the very last minute, we decided to give them a surprise,” related Ayesha, “When the children were on their way to the studio they were told that Khoobsurat couldn’t make it.” They were understandably crushed. During the filming of the show, Ayesha made her surprise appearance. “They were really shocked!” she laughed, “It was really nice. Those two girls were completely in awe. They were completely ecstatic.”

“I had no idea they were such big fans!” she said, “One of them wanted to be me. She had tried to dress up like me and accessorised her outfit with the same kind of bangles and rings that I wear on the show.”

While efforts like this do not of course fight the disease directly, they do provide moments of joy for those children who are fighting for their lives.

Cancer among children can occur suddenly, without any visible early symptoms. There is, however, a high rate of cure if detected early. One of the most common forms of cancer among children is leukaemia (around one third of all cancers afflicting children worldwide). These are followed by brain and central nervous system tumours, neuroblastoma, lymphoma, bone cancers, etc. The causes of childhood cancers are largely unknown but are usually attributed to ionising radiation exposure (perhaps due to parental occupation), specific genetic and chromosomal abnormalities, etc.

Children with Down’s syndrome and Aids have a higher risk of developing cancer. Children who undergo radiation from chemotherapy are also at a greater risk for developing secondary primary cancer.

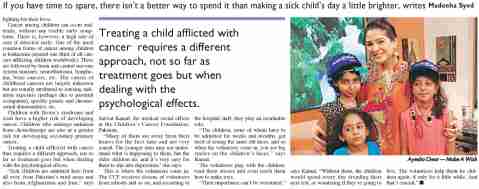

Treating a child afflicted with cancer thus requires a different approach, not so far as treatment goes but when dealing with the psychological effects.

“Sick children are admitted here from all over, from Pakistan’s rural areas and also from Afghanistan and Iran,” says Sarwat Kamal, the medical social officer at the Children’s Cancer Foundation, Pakistan.

“Many of them are away from their homes for the first time and are very scared. The younger ones may not understand what is happening to them, but the older children do, and it’s very easy for them to slip into depression,” she says.

This is where the volunteers come in. The CCF receives dozens of volunteers from schools and so on, and according to the hospital staff, they play an invaluable role.

“The children, some of whom have to be admitted for weeks and months, get tired of seeing the same old faces, and so when the volunteers come in, you see big smiles on the children’s faces,” says Kamal.

The volunteers play with the children, read them stories and even teach them how to make toys.

“Their importance can’t be overstated,” says Kamal. “Without them, the children would spend every day dreading their next test, or wondering if they’re going to live. The volunteers help them be children again, if only for a little while. And that’s crucial.”

Newspaper view: [Click for larger image]

Bakra online!

This Eid let your bakra come to you!

As Baqr Eid nears, you know that, at some point — before the animal slaughter-fest and never-ending family barbecues that dominate this holiday — you’re going to have to make a trip that no civilised man in the modern world should have to make. It’s time to go mad, cow hunting.

Let me paint a picture of what you know you’ll have to endure: a long drive out of the city to the bakra mandi; the stench of poop, hay and hooves combined with both human and animal sweat, hours and hours of searching and examinations (how many teeth, tongues and tails does it have?) coupled with impending migraines from all that haggling with the dealers. To top it off, the weather is only getting warmer. And those tents aren’t air-conditioned.

How far are you willing to go to personally see through every step of this madness? What if there was a way to bypass all of the above unpleasantness, save your nostrils some trauma, your car some potential piss and still get your bakra?

The answer to all your problems is one click away. Order your bakra online. Browse through catalogues that contain photos of sacrificial animals. We went through several websites that offer sacrificial animals online. One of them, an online marketplace Olx.com.pk has individual owners posting offers of their animals online and they do so throughout the year. Another website, Buy-bakra.blogspot.com had out-of-this-world photos of beautiful, seemingly blow-dried animals in scenic backgrounds to choose from. It appears defunct, however, considering that the last post on it was in 2009.

Two of the most comprehensive online animal buying websites one found was CowMandi.com and EidQurbani.com.pk. The former contains photos of animals from various farms, with each farm listed; along with these, are given various cattle-related trade events with one section of the website devoted to animals that are up for sale.

EidQurbani.com.pk, however, seems to cater exclusively to the Eid buyer. They have been in business for the last five years and have posted on their website that, “we offer pictures of animals alive and slaughtered to reinforce your confidence in us.” Animals are divided into different categories. Details regarding their size, weight, gender, price, etc. are all available. Bakras are priced between Rs19,500 and Rs26,500, while cows start from Rs60,000 with the most expensive one priced at Rs145,000. Bulls range from Rs56,500 to a whopping Rs212,000. To use the service you need to register an account and they take cash upon delivery of the ‘product’.

When one asked around, Mrs Parveen Khan, a 45-year-old homemaker, who has previously ordered her animal online, was quite satisfied with the service. “I didn’t know what to expect,” she said, “but I didn’t think there was any harm in trying. Plus, it’s not as if I was making any advance payments that I was at risk of losing. It’s cash on delivery and I had the bakra inspected by the neighbourhood butcher just to be on the safe side. I think it is a very convenient service to have.”

Faisal, 34, who runs his family jewellery business and belongs to Karachi’s Memon community, is open to the idea of ordering a bakra online instead of going to the mandi. “I’ve never enjoyed the process of taking a day off and going to the bakra market. For the past several years, my brother has been buying my bakra for me,” he said, “if the service is legitimate, and even if I have to pay a few thousand rupees extra, I would love to be able to order my bakra online.” He added that he wasn’t sure if the notion of an online bakra mandi would take off in Pakistan as for most of the people in his neighbourhood, the process of personally going to the mandi was an event they prepared and looked forward to. And later, they enjoyed parading their buy around fishing for compliments. The online bakra delivery system wouldn’t work for them, Faisal said.

“Hell no!” responded Asad, 27, a professional photographer, “I’m not big on Baqr Eid, but no matter how legitimate the service, I wouldn’t trust them to buy a bakra for me. You need to go to the mandi and see for yourself the condition and price of the animal you are going to buy.” That was an interesting response coming from a person who doesn’t feel strongly about the religious festival.

If the mere notion of making a trip to the bakra mandi fills you with dread, be a little adventurous and try something new. Go online, select your bakra, a delivery date, arrange for the payment and soon, the bakra of your choosing will be ringing your doorbell.

The pricetag

We’re number three! In terms of importing electronic waste, that is. That’s not necessarily a good thing.

By the end of 2011, an estimated one third of the world’s population was online. In Pakistan alone, 18.5million people use the Internet while another 107.8 million subscribe to various cellular networks. Statistics aside, it is hard to imagine life without communication technology.

According to a statement issued by the United Nations in 2011, there are over six billion mobile subscriptions in the world (one billion of these are in China alone) compared to a global population of seven billion. That’s a lot of mobile phones.

This global demand for electronic goods keeps growing, putting immense pressure on already scarce resources. Most Information Communication Technology (ICTs) such as computers and mobile phones are designed to have a lifespan of two years after which they have to be disposed of. Considering the numbers involved, this adds up to a lot of e-waste.

Around 20-50m tons of e-waste is generated every year and only 20pc of it is formally recycled. The rest is dumped in countries (like Pakistan) where there are little or no means of recycling e-waste properly.

Where does it come from and where does it go?

According to the report “E-waste imports and informal recycling in Pakistan: A multidimensional governance challenge” by The Royal Institute of Technology, Sweden, tons of e-waste is entering the country through the United Arab Emirates, Singapore and India — and these are only some of the routes through which e-waste arrives.

Pakistan is not only a signatory to the Basel Convention on the Control of trans-boundary movement of hazardous waste and their disposal, which forbids the movement of electronic waste from developed countries to developing countries, but is also a party to various other environment related conventions that are violated by the import and informal disposal of e-waste. These include the Rotterdam Convention on Prior informed consent for certain hazardous chemicals, Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, Vienna Convention and Montreal Protocol on Ozone depleting substances. None of this stops Pakistan from becoming the third largest importer of e-waste in the world, according to the above-mentioned report.

It goes on to mention that electronic waste enters Pakistan camouflaged as second-hand equipment (the equipment is often crushed to fit as much as possible into containers), donations and Afghan imports. Pakistan is the transit route through which e-waste imported by Afghanistan passes through, but most of the waste is sold in Pakistan before it reaches the Afghan border, so all of this tonnage enters the country and still manages to remain officially ‘under the radar’.

Why Pakistan?

Handling e-waste is becoming an increasingly lucrative industry in Pakistan. Equipment is graded for quality (A1 to D grade or scrap) with the best sold at a profit in local markets. The other main reason for Pakistan becoming a major dumping site for e-waste is cheap labour. The workers toiling away at dump sites come from extremely poor backgrounds and usually earn less than $2 a day. Compare that to the cost of $20 it takes to dispose off one’s computer in a developed country and you have a 100pc return on your investment. Handling e-waste is easy income for these workers albeit at the cost of their health. They aim for basic survival and concerns regarding health and sanitation take a backseat. Another reason for Pakistan being a prime site for e-waste is negligence and lack of interest by health and environment agencies.

How mishandling e-waste affects the environment E-waste contains precious metals such as copper and gold, the recycling of which includes manual extraction of copper wires from equipment, burning of cables and dipping of microchips and the motherboard in acid, known as an ‘acid bath’. This melts away its components leaving only precious metals behind, releasing toxins into the air, the earth and whatever is left behind is usually disposed off into the nearest river or water body, thereby causing serious environmental damage.

Chemicals washed off wires, acid, ink toners and other refuse seep into water bodies, accumulate with other toxins and eventually make their way into the sea; seriously affecting aquatic life … and those who eventually consume it.

In Karachi, the largest e-waste dumpsites are in Sher Shah and Lyari and so the waste from ‘recycling’ e-waste goes into the Lyari River that passes through mangroves. Recent reports point towards a heavy metal concentration in mangrove waters even though mangroves are natural filters of pollutants in the water, but there is a certain tolerance level that should not be exceeded.

More than skin deep

Most of the workers are aged between eight and 50 plus, and since they do not use any protective gear (suits, gloves or masks) when handling electronic items, they expose themselves to harmful chemicals by breathing them in as well as through their skin.

Electronic waste contains heavy metals, Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), flame-retardants and harmful chemicals such as lead, mercury and cadmium. According to a report by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) titled The global impact of e-waste: addressing the challenge even a small amount of exposure to the latter chemicals can cause severe neurological damage in pregnant women and children. Long-term exposure to lead also causes blood pressure in middle-aged men. These are just some of the health hazards that these workers expose themselves to. The workers either seem unaware of these hazards or believe that they have built immunity to them.

Authorities may wave off the industry by claiming that it operates ‘informally’, but it exists unregulated with all its dire repercussions and without checks and balances.

While neighbouring countries have introduced policies to clamp down e-waste entering their countries, the global level of this waste continues to increase — we can be sure that this industry isn’t going to die down anytime soon in Pakistan. It needs regulation and standard practises before irreparable and irreversible damage is done to both the environment and to the people working within these yards.

TOXIC ALERT Workers involved in recycling e-waste (especially those breaking cathode ray tubes) using rudimentary methods without any protective gear run the risk of inhaling particles that may contain barium oxide and phosphors. Those dealing with the shredding of bulbs, switches and lamps risk inhaling mercury contained in them. Brain damage is a side effect of exposure to mercury.E-waste workers are also vulnerable to lead toxicity. Lead causes neurological damage, and long-term exposure to lead can severely damage kidneys and learning disability in children. Muscle and joint pains and high blood pressure are also some of the side effects of exposure to lead.When a torch flame is used to burn e-waste, it releases Brominated Flame Retardants (BFR) into the air that can be inhaled by the worker burning them. Motherboards contain beryllium which is not only carcinogenic, but also causes skin warts and beryllium disease in which the lungs are affected because of exposure to beryllium.Burning wires to extract copper releases dioxins and furans into the atmosphere. These are known carcinogens and in adults can adversely affect reproductive abilities and changes in glucose metabolism and the immune system.

Newspaper view: [Click for larger image]

The O team

Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, Pakistan’s first and only Oscar winner, is chairing a committee of industry professionals who will be selecting Pakistani films that will be submitted to The Oscars for consideration in the Best Foreign Film category. Here she speaks to Dawn about why it took 50 years for Pakistan to decide to submit a film, her opinion of the local industry and the response the committee has received so far

In its entire history, Pakistan has only submitted two films for Oscar consideration. Both failed to secure a nomination. Director A.J. Kardar submitted Jago Hua Savera in 1959 and Khawaja Khurshid Anwar submitted Ghunghat in 1963. Since then the industry has submitted nothing. It’s been 50 long years since Pakistan sent its last film to the Oscars for consideration. That is a very long time.

Films have been made in Pakistan during that time; some of the more recent ones did pretty well locally as well as in the international film festival circuit. Why does Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, Pakistan’s only Oscar winner (in 2011 for her documentary Saving Face which she co-directed Daniel Junge), think it took this long?

“The onus to form a committee of this nature falls in the hands of the filmmakers and artists of that country, and not the Academy,” responded Chinoy, “While I am unsure of why we failed to submit a film for 50 years, I assume that it is due to our weakening film industry as a whole and a lack of interest on our part. It’s unfortunate that no one thought of forming this committee before but now that we have a competent committee we are anxious to move forward and send in the best entry from Pakistan.”

The committee is currently chaired by Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy. Other members include author Mohsin Hamid (The Reluctant Fundamentalist), director Mehreen Jabbar (Ramchand Pakistani), filmmaker Akifa Mian (Inaam), a prominent member of the film and TV industry Sameena Peerzada (Inteha), actor Rahat Kazmi and culture academic Framji Minwalla.

How was the committee formed? “We had to submit a list of committee members to the Academy who then vetted and approved our nominations,” informed Chinoy, “The Academy advised us to submit a diverse list of members, from directors and actors to academics and writers. We received approval soon thereafter and are now in the process of soliciting submissions for consideration for the 2014 award cycle.”

Considering that most of the committee members are active in the industry in one capacity or another, in a situation where the committee members have been active in a film project will they continue to judge submissions or are they expected to step down for that particular session? In such a situation, Chinoy informed, “the committee member will be asked to abstain from voting for that year.”

The committee placed its official call for submissions several weeks ago. How has the response been so far? “The response has been very heartening,” she enthused, “We have already had several inquiries and application forms have been emailed out. By forming this committee we have taken the first step, I have no doubt that one day in the near future a Pakistani film will be short listed for the Foreign Language Film award and do us all proud.”

New beginnings, hopes and challenges

“The Pakistani film industry is slowly experiencing resurgence; Pakistanis are going back to the cinema, new theaters are being built, and more students are opting for a career in the arts,” said Chinoy about the changing face of the Pakistani film industry. “Over the past two years, we have seen a significant rise in the number and nature of films being produced locally, from independent art films to our signature Lollywood song and dance thrillers.”

Speaking about the challenges faced by local filmmakers, she said, “We do however continue to struggle in terms of resources; our filmmakers do not have ready access to modern filmmaking equipment. Independent movies or movies with subject matter that diverge from mainstream Lollywood content have little commercial viability and we lack the academic institutions to teach our next generation the art and craft of modern filmmaking.

“Just like any other enterprise, our material is also subject to demand and supply, and thus I hope that an increased demand results in a renewed interest from potential financiers and academic institutions as well. It may take time but I have no doubt that the film industry will prosper if nurtured properly.”

A web edition of a prominent foreign publication claimed that 21 films have been released so far in 2013 in Pakistan. Considering that very few of them actually hit theatres or generated a buzz, in her opinion, does she consider that number accurate and as a truthful depicting of the current state of the cinema industry?

“Personally I do not see it as an accurate depiction of our current state of cinema, but I see it as a positive sign for what the future state of our cinema should be,” Chinoy responded, “As mentioned previously, one of our largest impediments is the lack of funding for film projects. While there are 21 films being released in 2013, I can say with some certainty that most of them will not have the funds for the necessary marketing and publicity needed to fill theatre seats come screening day.

“And this is what is most unfortunate about our industry; we have the talent who are striving to produce quality content but without the requisite industrial support to market their work, they will always face an uphill struggle making their films profitable. We need to encourage cinemas to show Pakistani independent films and encourage distributors to market them.

“That being said, it is encouraging to see the next generation of filmmakers are proactively using social media to create word of mouth buzz for their films, despite YouTube bans and other limitations. I think it’s a very positive sign for our film industry that 21 films are being released this year and I wish their respective creators nothing but the very best in their careers.” — Madeeha Syed

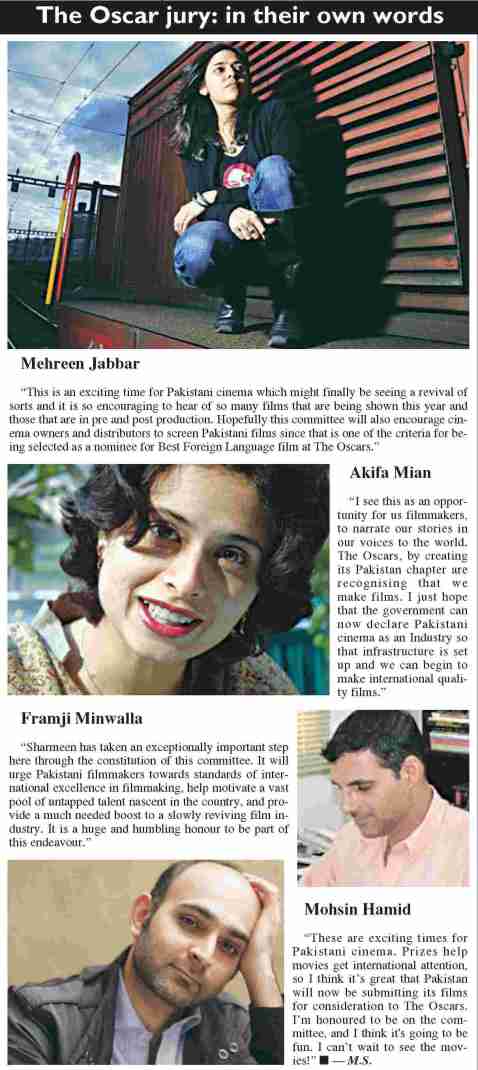

The Oscar Jury: in their own words

Mehreen Jabbar

“This is an exciting time for Pakistani cinema which might finally be seeing a revival of sorts and it is so encouraging to hear of so many films that are being shown this year and those that are in pre and post production. Hopefully this committee will also encourage cinema owners and distributors to screen Pakistani films since that is one of the criteria for being selected as a nominee for Best Foreign Language film at The Oscars.”

Akifa Mian

“I see this as an opportunity for us filmmakers, to narrate our stories in our voices to the world. The Oscars, by creating its Pakistan chapter are recognising that we make films. I just hope that the government can now declare Pakistani cinema as an Industry so that infrastructure is set up and we can begin to make international quality films.”

Framji Minwalla

“Sharmeen has taken an exceptionally important step here through the constitution of this committee. It will urge Pakistani filmmakers towards standards of international excellence in filmmaking, help motivate a vast pool of untapped talent nascent in the country, and provide a much needed boost to a slowly reviving film industry. It is a huge and humbling honour to be part of this endeavour.”

Mohsin Hamid

“These are exciting times for Pakistani cinema. Prizes help movies get international attention, so I think it’s great that Pakistan will now be submitting its films for consideration to The Oscars. I’m honoured to be on the committee, and I think it’s going to be fun. I can’t wait to see the movies!” — M.S.

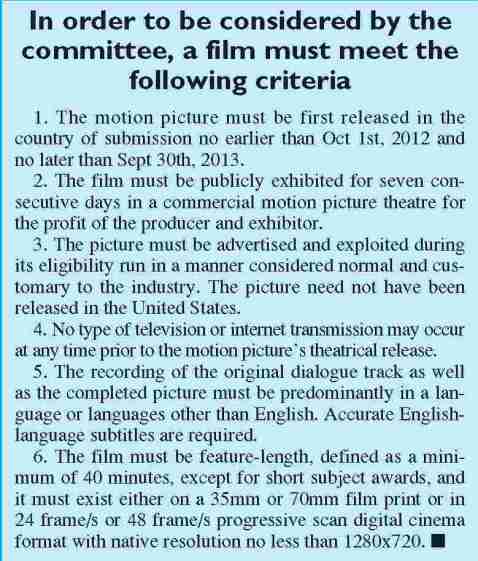

In order to be considered by the committee, a film must meet the following criteria

- The motion picture must be first released in the country of submission no earlier than Oct 1st, 2012 and no later than Sept 30th, 2013.

- The film must be publicly exhibited for seven consecutive days in a commercial motion picture theatre for the profit of the producer and exhibitor.

- The picture must be advertised and exploited during its eligibility run in a manner considered normal and customary to the industry. The picture need not have been released in the United States.

- No type of television or internet transmission may occur at any time prior to the motion picture’s theatrical release.

- The recording of the original dialogue track as well as the completed picture must be predominantly in a language or languages other than English. Accurate English-language subtitles are required.

- The film must be feature-length, defined as a minimum of 40 minutes, except for short subject awards, and it must exist either on a 35mm or 70mm film print or in 24 frame/s or 48 frame/s progressive scan digital cinema format with native resolution no less than 1280×720.

Newspaper view: [Click to view larger image]

Burning down the house

Nadeem H. Mandivwalla, the owner and managing director of Mandivwalla Entertainmant, Pakistan’s largest film distributors and owner of several cinema houses across the country, talks about the importance of cinemas, the changing shape of the film industry, the evils of piracy and the potential for local films to go global

Q. Last year, violent mobs set six cinema houses in Karachi and Peshawar on fire. Why do you think films are seen as an evil in society and why do people take their anger out on them?

N. Mandviwalla: It’s not just cinemas, art is seen that way. Why cinemas? Because films are the strongest medium of storytelling through which you can communicate an idea, a message. Have you ever seen people take out their aggression on cable?

For 30 years, Indian movies have been shown in this country through video, dvds, cds etc. The entire country has not objected to it. But before 2007, whenever we asked anyone whether Indian films should be shown in cinemas in Pakistan, they always said they shouldn’t be.

We have a national problem: we like to do things illegally, but not legally. When you do things illegally, it damages yourself, not anyone else. As long as these films were coming in illegally they were destroying our industry, now they are coming legally and you can see the result. You have been able to build cinemas and show people the films they want to see.

And the public sees Indian films because they share a language in these films. If the public was speaking Chinese, we’d bring in Chinese films. Foreign films have become a great source now and you can see that in the rebuilding of cinemas.

Production of local films finished because you finished your cinemas. Cinemas are the shop through which you show your films.

Q. Do we have enough cinema houses for the film industry to really revive itself?

N. Mandviwalla: No, we don’t. For that we need a minimum base of a $2m market. We have reached up to $1m. That requires a 100pc improvement. That means a very big film has to gross a minimum of Rs20 crore in Pakistan.

Q. Compared to foreign films, are local films doing as much business in Pakistan or running for as long?

N. Mandviwalla: Local films have one major advantage: they are not pirated as long as they are running in Pakistan. The moment they go abroad, they are pirated. It always happens from abroad even though this is the biggest market for pirated films.

We’re advising every Pakistani production not to release their films simultaneously in local cinemas and abroad. Bol (2011) released in Pakistan eight weeks ahead of its release in India. The minute it released in India, the film came on YouTube.

Q. There is a newer trend of building cinema halls in shopping malls in Pakistan. Some get it right; others get it wrong, what is your opinion on this approach?

N. Mandviwalla: It’s just the Atrium cinemas that are properly designed. While building the mall, they had pre-designed the space for the cinema and automatically kept all of the provisions that were needed. Every other new mall you see nowadays has a cinema as an afterthought. Because Atrium has become a success, every mall feels the pressure to complete the package. That’s not the right thing to do when building a cinema. They will automatically feel the effects of that in the longer run.

You are getting more and more competition. The standard set by the Atrium is very high. The public has a lot of choice now. They will make the journey anywhere where they get their money’s worth.

Some of the malls have gone back to the drawing board. That is the right way to go. They are considering how to put up cinemas in the proper manner and when these cinemas come up, you will see the difference.

Q. Now that newer filmmakers are entering the industry and there is an increasing trend of making films, how do you see the industry shaping up?

N. Mandviwalla: I would just like to see Pakistanis making films. It doesn’t matter to me what kind of films. The quality of cinema being made in Pakistan has been high, so the production of films has to go up. You are now aligned for that kind of cinema.

This automatically gives you access to the world, when you make the kind of films that can be shown anywhere in the world. People aren’t going to see anything substandard now.

Newer filmmakers are very conscious and know how to deliver quality. Now the question is whether as directors, they are able to deliver strong content. You can’t keep asking for exceptions like Shoaib Mansoor.

You have to come into the flow and start making films. You will get it wrong the first time but the second time you won’t. Whether good or bad, just make films.

Q. Is there enough of an audience to come to these cinemas?

N. Mandviwalla: On the contrary, we have too many films coming in and we don’t have the space. We don’t have enough cinemas to cater to them. We have to make more cinemas.

Films have to make money and that money comes through the cinema. That’s the channel. There were many films that came out in the last 30 years we never thought we could show but today we can, because now we have an audience for them.

I could never imagine we’d have an audience for animated films. Today those animated films are doing a business of $100,000 to $200,000 here. That clearly means the audience is there.

Q. India has been doing away with their old cinemas and have been building newer cinemas in their place…

N. Mandviwalla: And you can see the result, they have come up to a Rs200 crore market. At the moment, Pakistan’s target is just 10pc of that. If you go up to 20pc, you will become the biggest market after India for Bollywood. That can work vice versa as well.

If they have a market of Rs20 crore here, we we have a potential market of Rs200 crore there. That will only happen once you make good quality films, the kind of which they are coming up with. You will start penetrating their market and that is where the real trouble will start.

Q. How so?

N. Mandivwalla: Because even Hollywood hasn’t been able to penetrate their market the way we potentially can. And they know that. And Pakistan, can for the same reason their films can penetrate our market: you are making films in the same language that is spoken in both countries.

If the industry continues to grow at this rate, 10 years down the line, I would like to see how Bollywood reacts. We have been very liberal when showing their films and we have a big heart. Let’s see if they will respond with the same.

Q. What do you consider as one of the major deterrents in the development of our local film industry?

N. Mandviwalla: That would be irregularity. The day any government can start controlling that your market can jump up to Rs50 crore. That’s the kind of difference it will make.

I remember going to Dubai in the 1980s, there were only two English cinema houses there and they used to show films that were six months old. Nobody used to go there because the hub of pirated videos was Dubai at that time. After about 10 years the Dubai government decided this was a business of theft and it had to be stopped and regulated.

Today, Dubai has 100 screens alone and their population, tourists included, is just that of a small locality in Karachi. If they can have that, imagine the kind of growth you can have in this country.

Irregularity is damaging our own country. It’s not damaging anyone else. It didn’t stop Bollywood or Hollywood from progressing because there is rampant piracy here, it damaged us.