BYOP: Buy your own politician

The politics behind the new “top secret toys for highly mature adults!”

First you could eat them (‘Nawaz Sharif’s Chatpata Churan’ and ‘Tabdeeli Ka Nishan Imran Khan Churan’ — both purely Lahori creations). Then you could flash them (remember the cheap torch-equipped lighters that would project the image of your chosen political leaders on the wall!) And now, you can play with them, pummel them or just watch their oversized heads wobble.

Anything is possible in ‘Naya Pakistan’, especially when a budding new enterprise comes up with an ingenious concept: buy your own politician.

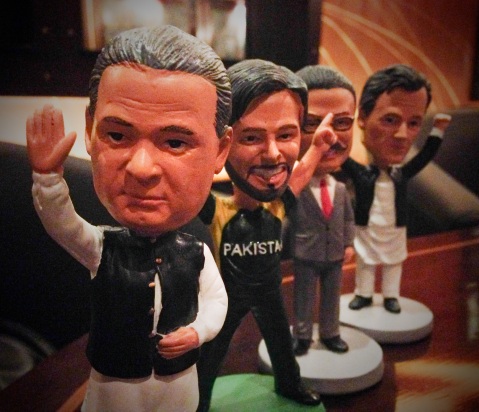

“And why not?” ask the men behind Bobble Dobble, a new online venture that sells limited-edition bobblehead dolls in the shape of our politicians. “They’ve bought and sold us many times, so now we’re going to sell them instead. We wanted to show these people, who were supposedly ‘in charge’ of us, in a fun light.” Their business was only 1.5 days old when I met them, and they had already gotten 20 orders — each one for a multiple set of dolls.

It was at a café in Zamzama (the location of which will be kept secret for security purposes) where we met the men behind this ‘daring’ yet loveable enterprise. Unwilling to use their real names, they chose their own aliases and shall henceforth be referred to Victor McPherson (Irish mafia), Don Pablo (Ecuadorian lover) and Mr Mister (mashoor rap-star). Yes, seriously.

On top of the table is their first batch of toys: a strangely slim Nawaz Sharif waving his hand, Shahid Afridi with both his arms up in a permanent state of triumphant joy, Imran Khan flashing a V sign (construe what you may from this) and Asif Zardari with his perpetual pearly-toothed smile. In fact, this particular Zardari had the ends of his moustaches fashionably tweaked upwards. It turns out that each Bobble Dobble doll is unique in its own way. In short: if you change the doll, you get a new moustache.

But how did they miss out on creating an Altaf Hussain doll? “Altaf Bhai ko kaun khareed sakta hai?” asked McPherson immediately, looking over his shoulder. Point noted.

Their website states that they sell ‘top secret toys for highly mature adults’, so what made them enter the adult toy industry, I ask? The men burst into laughter. Five whole minutes later, and they’re still laughing. “This is basically humour for adults. If you’re an adult, you’ll understand it,” said McPherson, wiping tears from his eyes, “that’s why we’ve classified it as ‘toys for adults’.”

“These toys are supposed to make your day better,” said Mr Mister, “if at the end of the day you’re really angry and frustrated at these politicians, you can take it out on the dolls.” Oh, okay. “But we don’t encourage violence of any sort!” he added forcefully.

Their website states, ‘You can put them on your car’s dashboard, office desk, or burn them in protests. We don’t care once you’ve bought them.’ “Yes, absolutely,” said McPherson, delving into how the idea of creating bobblehead dolls on politicians came about.

It all started some time ago when he was driving down a street in Lahore and came face-to-face with a poster of Asif Ali Zardari. That led this young man to question: “If politicians can exploit us to make money, why can’t we exploit them?” And thus, a Pakistani bobblehead dream was born.

Meet a real life Bobble Dobbler

Shakir Husain, (almost) 38, is a Karachi-based entrepreneur and storyteller who dabbles in capacity building. When he first came across the toys on a social media website, not only did he decide to place an order of dolls for himself, but he also wanted to share the love: he ordered extra units as presents.

What compelled him to place his order? Who did he buy? “It seemed like something fun and interesting with a political bent,” responded Husain, “I bought the three politicians and skipped out on Afridi.”

Did he think he got a fair bargain? “A thousand bucks a pop seems quite fair,” said the satisfied customer.

How did it feel buying a politician? Did he feel a surge of power rush through his veins? Like the ‘king of the world’, maybe? “If only they came so cheap,” he lamented, “When buying a politician, one must ensure that it’s one which can get some SROs passed.”

Did he see his favourite politicians up for sale? Who did he miss and would like to see up for grabs in the future? “Unfortunately, I didn’t,” Husain responded ruefully, “I would like to see Wasi Zafar, Abida Hussain and Shaikh Rashid. I think Benazir Bhutto, General Zia, Ghulam Ishaq Khan, Nawabzada Nasrullah and General Musharraf should all be there.” Evidentially, he was just full of helpful suggestions. “We need to learn how to laugh at ourselves,” he finished.

What exactly is he planning to do with the politicians err … dolls? “I’m going to see how they work out,” he said, “I’m going to put the three politicians in my kid’s room so they understand why they need to study and do well in school.” And hence begins a family tradition that is sure to be passed down for generations to come.

Fashion conscience: Is their blood on your shawl?

Imagine wearing four dead animals around your shoulders. That’s the average number of Chiru antelopes it takes to make just one shahtoosh shawl. And the Chiru, today, is on the brink of extinction.

THE SHAH OF SHAWLS

Shahtoosh literally means the ‘king of fine wool’ in Persian. It is made from the down fur of the Chiru antelope found in India, China and Nepal. It lives at an altitude of 5,000 metres and above and has extremely light fur that is incredibly warm as well.

Chiru are shy and solitary by nature that makes creating an accurate assessment of their population difficult.

Because of its fine quality, it was also hard to weave into a cloth but the artisans of Kashmir, who were already making fine pashmina shawls (made from the wool of the pashmina goat), had the skills to weave this fine fur into a fabric. It is said that Mirza Muhammad Haider Dughlat, who ruled Kashmir from 1540 to 1551, was the first one to introduce shahtoosh weaving to the region. To this day, this craft of weaving fine pashmina and shahtoosh shawls is almost solely restricted to this region.

With their arrival into the subcontinent, the British were the first ones to recognise the importance of, and introduce, fine pashmina and shahtoosh shawls to the world. And with the decline of the popularity of mink and fur coats in the United States in the early 1980s, the shahtoosh took their place as a highly coveted and prized wardrobe accessory.

Today, a shahtoosh shawl can sell for anywhere between Rs 300,000 to Rs 1,500,000 depending on its quality and embroidery. A shahtoosh shawl is so fine that a standard one-by-two metre shawl can be pulled through a finger ring.

Unfortunately, unlike the pashmina shawl, which can be made by shearing off wool from live pashmina goats, the down fur of the Chiru can only be obtained by poaching and murdering them. Due to this trade, the animal has almost become extinct in Nepal.

CHIRU: HERE TODAY, (ALMOST) GONE TOMORROW

According to a World Wildlife Foundation (WWF) estimate, there are around 75,000 to 100,000 Chirus living in the wild today.

“That is not a huge population for an antelope, especially a slow-breeding one like the Chiru,” said Uzma Khan, the Director Biodiversity at the WWF in Pakistan, “they give birth to one offspring per year and half of those die within two months of their birth.” In the past 20 years alone, there has been an alarming 50 per cent decline in the antelopes’ population.

DROP THAT SHAWL: THE BAN ON SHAHTOOSH

“Usually provincial wildlife laws prevent exploitation of local species and for special exotic species there are bills,” related Uzma Khan. Shahtoosh was banned internationally when the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (Cites) came into force in 1975. It is banned in over 150 countries around the world. Possessing a shahtoosh shawl (without a permit) in these countries can result in the imposition of a heavy fine and imprisonment.

A high-profile campaign from the mid to late 1990s in the United States where several celebrities and socialites were targeted and asked to surrender their prized shawls popularised the ban. It was banned in India in 1991 and formally in Jammu and Kashmir in 2000.

“It was approved early last year,” related Uzma Khan talking about where Pakistan stood on the ban, “The ban was made under a convention of which Pakistan is a signatory.”

What about those who already possess a shahtoosh shawl? “If it was bought as a personal item many, many years ago, then it’s fine to keep one,” responded Uzma Khan, “But if you have shahtoosh and intend to use it for commercial purposes, then you require a Cites permit. It’s illegal all over the world.”

DEMISE OF A CENTURIES OLD FAMILY TRADITION

When the trade was banned in Jammu and Kashmir in 2000, thousands of workers not only lost their livelihoods but also a very important tradition — the craft of weaving shahtoosh shawls had been passed down through generations for centuries.

“When a species has declined to an extent that its trade has been banned, that essentially means that it was badly exploited,” said Uzma Khan, “Conservation is never against taking animals as long as it is done sustainably. WWF supports trophy-hunting programmes because they sustain communities and protect wildlife. There are other options (perhaps other animals such as sheep) that these families can adapt their skills and trade to.”

CAN THESE ANTELOPES BE BRED IN CAPTIVITY?

Advocates of the shahtoosh industry claim that a possible solution would be to breed the antelope in specialised farms to increase their population.

“Chirus are solitary animals that are found on mountains and steep slopes,” responded Uzma Khan to the suggestion, “It would be very difficult to breed them because they live in a very special environment that is hard to replicate.

“Animals that are solitary, as the Chiru, are usually very shy. Experience tells us such species are hard to breed,” she emphasised adding that efforts to breed the Grey Goral, another species of small mountain antelope, found in Pakistan and on the brink of extinction, haven’t been successful.

ALIVE AND UNDERGROUND

A lot of alleged shahtoosh (or ‘toosh’ as they are also called in the local lingo) shawls that are sold in the market are heavily mixed with cashmere or are cashmere shawls being sold to unsuspecting customers. But that doesn’t mean the trade in shahtoosh has ceased completely.

Despite the ban, the underground trade in shahtoosh shawls continues to this day. These precious shawls are often smuggled through Tibet, Bhutan and China, and are still highly coveted by the members of the world’s rich and powerful. In some places, especially in Kashmir, it is a tradition and considered a matter of great pride and prestige for a newly wed bride to have at least one shahtoosh shawl in her dowry.

Before you get tempted to spend money on a shawl so exquisite that it can pass through a ring easily, with embroidery so fine that it makes you wonder whether a divine hand was involved in making it, ask yourself: is there blood on your shawl?

Newspaper view: [Click for a larger image]

From behind the barbed wire

On December 16th, 1971 The Instrument of Surrender was signed jointly by Lieutenant-General Amir Abdullah Khan Niazi, the last governer and the supreme commander of the Pakistani army and Lieutenant-General Jagjit Singh, the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief of the Eastern Command of the Indian army, signaling the end of the Indo-Pakistan 1971 war. A new nation, Bangladesh was born out of the ashes of what was formerly known as East Pakistan.

The Fall of Dhaka, as this moment in history is also known, resulted in the surrender of almost 93,000 Pakistani army men stationed there to the Indian armed forces. Retired major Mohammad Iqbal Mirza was one of them.

He was in his forties back then. Now at the age of 88, retired major Mirza is a tall lean man who believes in going on water fasts and fruit diets. They must be working because he is an incredibly active man and appears quite healthy. He seems unaffected by any of the frailties of old age. He was a prisoner of war in India for almost three years.

He was commissioned to go to East Pakistan right before the war broke out. He was stationed in the Martial Law Headquarters in East Pakistan. “I was a part of the administration focused inside the cities,” he related, “although I believe our soldiers who were on the frontlines fought very bravely.”

What was it like living as a West Pakistani army man in East Pakistan at that time? “I was afraid of going to sleep. I would spend my nights sitting in a chair with a grenade in my hand.” Why? “Because of the Mukti Bahini of course!” he exclaimed, talking about the guerrilla group in Bangladesh that fought the Pakistani army stationed there. “We had nothing to be afraid of during the day as they never dared to attack in broad daylight,” he said emphatically, “They usually attacked at night, under the cover of darkness.”

Following the fall of Dhaka, he was one of the 93,000 army troops who surrendered as POWs to the Indian army. They were held in camps with barbed wire boundary walls. The Indian troops would patrol the boundaries at night with watchdogs.

Despite all these measures there were quite a few successful escapes.

What was the worst that could happen? “That you could either be shot or your nails could be pulled out,” he said gesturing with his hands to depict the latter consequence, “but that usually happened only if you tried to escape from the camp.”

Did a lot of prisoners of war attempt to escape? “Oh yes. Not officers who were as old as I was.” You were in your forties, that is not old? “It is by army standards. It was mostly younger officers who would attempt to escape. You tend to take more risks when you’re young. We knew there were several people who were trying to dig a secret tunnel. They would cover the opening up whenever they weren’t digging or when they felt it would be discovered.”

Did it work? “No. Unfortunately, the tunnel they were digging caved in. But we had heard that in the camp beside ours, several people had managed to successfully build a tunnel and they escaped.

“Two men managed to escape from our camp. They were a little crazy if you ask me. They were young men who broke through and climbed over the barbed wire walls around our camp. Their hands were badly injured and they had cuts all over their bodies. Unfortunately, when they got out, they ran into a check post run by Indian soldiers and were caught. The soldiers shot one of them and returned the other alive to tell the story.”

But there were exceptions to the ‘good’ manner in which the Indian army treated the POWs. “Indian senior army officers used to come to our camp once a month and give us a talk on discipline and matters of their interest,” he said, and went on to relate an episode where, during one such session, a Pakistani army man lost his temper and spoke rudely to the Indian officers. He was later taken away, beaten up and put in a small cell where they stored hand grenades; there was only enough room for one man to stand. The Pakistani prisoner had to stand perfectly still the entire night or risk being blown up. “The officer on his return couldn’t walk or move properly for almost ten days,” Mirza remembers.

Overall, however, the prisoners were treated well; they were kept in accordance with Geneva conventions and everything was fine as long as they behaved themselves and did not try to escape. “There was a section where women and children prisoners of war were kept and we asked that one of our meals (we were given a sepoy’s ration of pulses, vegetables and mutton) that included meat be distributed to them — as army personnel we had greater privileges than they did. The war was costing the Indian government heavily in monetary terms!”

The Simla Agreement signed between India and Pakistan on July 2, 1972 laid down the rules that the two countries would follow when governing their future conduct with each other. The original agreement, however, did not mention any POWs.

In 1973, a supplementary Simla agreement on repatriation was signed upon which India released almost 90,000 POWs and allowed them to return to Pakistan.

When retired major Mirza returned, Lahore was his first stop. Everyone who returned had to submit an account of their experience and observations about their colleagues at camp. Anybody under the slightest suspicion of being ‘turned’ by the Indian army was essentially fired from service.

“Yes, some might have used this opportunity to settle a personal vendetta. Someone, who had an issue with me at camp, once complained that I frequented the offices of the Indian soldiers regularly. I was fond of reading and the Pakistani officer I would register my requests to would direct me to the relevant department to select the books I wanted. I was questioned about it, I responded honestly. I always followed protocol and there were people who could vouch for me, so I didn’t get into any trouble.

“Throughout the time I was away as a prisoner of war, the Pakistani army paid my monthly salary to my family and took care of them. After returning to Pakistan, I got to go home for a month as a ‘vacation’ and was then commissioned the Karakoram highway near the China border. Life went back to normal once we came back to Pakistan.”

Newspaper view: [click for larger image]

Shah Jehan mosque: A mesmerising symbol of gratitude

Thatta was once a centre of learning and commerce. It was the capital of Sindh for almost 95 years when the mighty Indus River flowed next to the city. The ancient banks of the Indus River, before it changed its course, can still be seen from near the Makli hill. The Makli hill is home to one of the two things Thatta is most famous for: the Makli necropolis (one of the largest in the world). The other monument that Thatta is famous for is the Shah Jehan Mosque.

The Shah Jehan Mosque was built during the reign of the Mughal Emperor Shah Jehan in 1647 and has been on the tentative UNESCO World Heritage Site list since 1993.

After Emperor Jehangir, Shah Jehan’s father, banished him from Delhi, Shah Jehan sought refuge in Thatta. The construction of this mosque represents Shah Jehan’s gratitude towards the people of Thatta for giving him shelter during that difficult time.

It is barely a two-minute drive from the Makli necropolis. The road leading to it, which was intact last year, is now in a state of disrepair.

Outside and inside the main courtyard of the mosque, there are several streetside vendors that have set up shop, selling everything from small souvenirs, colourful bangles and what not. The fountains of the mosque are dry.

The mosque was built in a similar manner to that of a Mughal courtyard (which lies right outside the main mosque’s premises). What separates it from traditional Mughal architecture is that instead of three large domes, there is only one main dome in the prayer hall as well as the fact that the glazed tile mosaic design belongs to the Timurid School of architecture — as is the employment of a large number of pishtaqs (a high arch set within a rectangular frame). Also red bricks have been used in the construction of the mosque rather than pink sandstone from Jaipur, which was a more common ingredient in Mughal architecture.

The mosque represents an era in Thatta where tile decoration was at its peak. The ceilings bear testament to that as beautiful mosaics adorn the inner side of the two main domes. The tile work is predominantly in blue with several other colours, such as green, red and violet, added in sporadically to offset it. The colours provide a somewhat soothing effect from Thatta’s unforgiving summer sun. What is interesting about the mosaic is that there are very distinct star motifs, which, when arranged together form a vision of a starry sky arranged around a sun — day and night coming together as one.

The Shah Jehan Mosque is known for the sheer number of its domes — over 100 — the largest number of domes in a mosque in the world.

Architecturally the mosque has been built keeping in mind the acoustics of the area — a person speaking at one end of the mosque can be heard at the other end without the use of a loudspeaker.

This beautiful 17th century structure is one of the best-restored and well-maintained heritage sites in Pakistan. If the Makli necropolis is the crown of Thatta, the Shah Jehan Mosque is its most precious jewel.

Newspaper view: [click for larger image]

Afghanistan’s 2,000-year-old treasure

It’s like a scene right out of an Indiana Jones’ film: a dozen or so men packed away precious 2,000-year-old gold ornaments and jewellery in toilet paper, sealed them in plastic bags, labelled them and signed a piece of paper as witnesses. They then placed them inside six safe boxes that were locked inside an Austrian-built vault at the Arg or the Presidential palace in Kabul. The twelve men were the tawildars – key holders without whom the vault could not be opened. The vault contained a 2,000-year-old treasure from the Bactrian Empire – a people about whom very little is known – also known as the Bactrian Hoard.

It’s like a scene right out of an Indiana Jones’ film: a dozen or so men packed away precious 2,000-year-old gold ornaments and jewellery in toilet paper, sealed them in plastic bags, labelled them and signed a piece of paper as witnesses. They then placed them inside six safe boxes that were locked inside an Austrian-built vault at the Arg or the Presidential palace in Kabul. The twelve men were the tawildars – key holders without whom the vault could not be opened. The vault contained a 2,000-year-old treasure from the Bactrian Empire – a people about whom very little is known – also known as the Bactrian Hoard.

It was the year was 1989. Afghanistan was at war with the Soviet army and the Kabul Musuem, where the treasure was originally kept, had been used as a military base and had been shelled repeatedly in previous years. In the onslaught, most of its precious artefacts had been destroyed, looted or stolen with only a small percentage salvaged or transferred for safekeeping. The then president of Afghanistan, Mohammad Najibullah Ahmadzai, officially closed down the museum in 1989 and transferred its holdings to three locations. One of those would keep the Bactrian Hoard safe for more than 25 years.

A Russhain archaeologist, Vicktor Sarianidi, had discovered the Bactrian Hoard in 1978 in Tillya Tepe or the Mound of Gold, which is located in a province in Northern Afghanistan. He had gone there after hearing rumours of a gold man buried inside a gold coffin and instead came across a 4,000-year-old temple. The temple contained the tombs of five women and one man.

Archaeologists believe that a nomadic tribe from Bactria had buried their kinsmen sometime in the first century C.E. Four of the nomads had their heads facing north and two had coins in their mouth – toll for Kharon (the ferryman of the Greek god of the underworld, Hades) to carry them across the Styx river that separated the living souls from the dead.

Between 1978 and 1979 Victkor Sarianidi and his team transferred the their precious find to the Kabul Museum. But a year after the Bactrian Hoard had been discovered, the country broke out into war with Russia and eventually the artefacts in the museum had to be moved to safer places. Many artefacts from the museum were lost, looted or destroyed in the ensuing war.

Eventually, the Bactrian Hoard was believed to have been lost forever. Many theories circulated regarding what had happened to the treasure. One was that it had been melted down or sold in the black market. Another was that it had been smuggled to Moscow. There was even a theory that stated that the Taliban tried blowing up the vault where the Hoard was stored before American forces attacked Afghanistan in 2001.

It was in the August of 2003 – 25 years after the Bactrian Hoard had been discovered and 14 years after it had been secretly locked in a vault at the Arg – that Hamid Karzai’s government announced that the treasure had been found and invited archaeologist Fred Hiebert to validate the hoard. Hiebert carried with him Sarianidi’s original field notes and he along museum specialist Carla Grissman travelled to Afghanistan to find out whether the Bactrian Hoard really did exist as they were told. They were not going to be disappointed.

There was a problem though – the tawildars who were needed to open the vaults were missing and no one knew where they were. “Only 13 to 20 people knew about the treasure and as fighting between different groups got worse we decided not to tell anyone about it,” Omara Khan Masoudi, who was one of the original tawildars and is now the director of the National Musuem in Kabul, said in an interview, “When the Mujahideen took power, some went to Pakistan, some went to Iran and some were killed. Only a few of us remained in Kabul.” Faced with the challenge, Karzai appointed a judge as a substitute tawildar and the vault was opened.

Soon after the perfectly preserved gold was verified arguments broke out over who would get it first. It was decided that the Hoard would be exhibited in various countries in Europe and in the United States. Some of the original tawildars also travelled with the Hoard and kept vigilance over it. One of them, Abdullah Hakim Zada, stated in an interview that he had never imagined there would be civil war followed by Taliban rule and worried that they hadn’t used the right material for the Bactrian Hoard to be kept in storage for so long.

“The story of the hidden treasure is like the story of Afghanistan,” said Said Tayeb Jawed, who was then the Afghan ambassador to the United States, when the Bactrian Hard went on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. “It’s about precious culture and traditions covered by the ashes of war and neglect. You don’t know what remains under the ashes, and when you see the glitter of gold, you almost can’t believe it.”

With its tumultuous, war-torn history, Afghanistan is known as the graveyard of empires and is rich in archaeological sites – many of which have not been excavated and which date back to a pre-historical era. Sadly, this is being exploited by looters who have been buying and digging into vast areas of land with the intent of pillaging the sites and smuggling out artefacts that are sold in the global underground antiquities market.

The Bactrian Hoard is important because it enable archaeologists to understand the time that passed between the decline of the Greco-Bactrian Empire and the rise of the Kushan Empire in the region. There are very few known archaeological finds from to this era. The Bactrian Hoard is considered to be one of the greatest archaeological finds of the 20th century.

Newspaper view: [click for larger image]

First lady: The Flower of Bombay

A young Ruttie

“I have loved you my darling as it is given to few men to be loved…”

– Rattanbai (Ruttie) in her last letter to Mohammad Ali Jinnah (October 25, 1928)

Not enough is written about the woman who was the chosen companion of the founding father of Pakistan. And only a handful of books have been published about her life. Rattanbai ‘Ruttie’ Petit (she officially became Maryam Jinnah after her marriage to Mohammad Ali Jinnah although she never actually used that name) was born on February 20, 1900; she was the only child of Sir Dinshaw and Lady Dinabai Petit.

The Petits were one of the wealthiest Parsi families of Bombay and their home played regular host to the crème de la crème of high society — ministers, intellectuals, poets, businessmen and prominent lawyers all gathered at their place to engage in stimulating debate and to socialise. It was in this environment and among such people that Ruttie grew up.

The ‘Flower of Bombay’, as she was called, was a force of nature — well read and mature beyond her years. She had three passions in her life: books, clothes and pets, and was somewhat spoiled by her parents who indulged her every whim. From a very young age, Ruttie was a natural charmer, beautiful, witty and obstinate, having an independent nature.

At the same time she was an incredibly soft-hearted person, generous, an ardent humanitarian and often spoke out against the ill treatment of animals. She was politically aware but rarely engaged in politics. Her love for fashion had established her reputation as one of the most well-dressed women in Bombay’s high society.

In the summer of 1916, Sir Dinshaw Petit invited a young lawyer, who he thought had a very promising career ahead of him, to spend a summer with his family in Darjeeling. Ruttie had met this lawyer on occasions when he came to their house to attend some of their dinner parties but it was during this trip that she got to know him better.

The lawyer was Mohammad Ali Jinnah, a resolute bachelor and 24 years her senior, but discovered that he and Ruttie shared quite a few similar interests: they both loved horse riding, books, were nationalists and harboured a healthy curiosity about the world around them.

Two years later, on April 19, 1918, at the hands of Maulana Nazeer Ahmed Khajandi at the Jamia Masjid in Bombay, Ruttie embraced Islam. Clad in a sari, bringing with her only her pets from her old life, she left her family to be with Jinnah. They married at his residence, South Court on the upscale Malabar Hill, and spent their honeymoon in Nainital.

Soon after her wedding, Ruttie busied herself with redecorating South Court and building up her wardrobe of finely tailored saris and suits.

She stood by her husband through thick and thin though her foray into anything that remotely resembled politics was short lived.

In May 1919, Ruttie was slated to speak at the first All India Trade Union Congress and she delivered a speech that was both eloquent and forceful. But the experience made her realise that facing an audience and speaking to them was no easy feat. That was the only public speech she ever gave. However she was very active in social welfare spheres.

Other than her efforts on behalf of animal rights, Ruttie worked extensively to improve the living conditions of the women working in the brothels of Bombay. She was concerned for the welfare of the children living in that district as well and with the support of her friend, Kanji Dawarkadas, pushed forward a Bombay Children’s Act to the Bombay Legislative Council in 1921. The act was passed in 1924 and enforced several years later.

She and Mohammad Ali visited England in May 1919; as a couple they often went out for walks, to the theatre and to the opera. Their daughter, Dina, who was named after Ruttie’s mother, was coincidentally and perhaps ominously born on August 14, 1919.

As Jinnah’s political career became more demanding he had less time to spend with Ruttie; it was around this time that Ruttie’s health also began to deteriorate. She was diagnosed with colitis and exasperated her doctors by not heeding to their advice. Soon, her illness became chronic.

Although she kept busy — she read as many books on the metaphysical as she could, went to theatre and the movies, and had friends over for dinner — she felt lonely and neglected. Her health continued to deteriorate; from 1926 through 1928 she was restricted mostly to bed.

Accompanied by her mother, Ruttie went to England in 1928 and later to Paris where she was admitted at a clinic in Champs Elysee. She was in a semi-comatose condition there and a visitor remarked that she would often whisper the following lines from Oscar Wilde’s The Harlot’s House: “And down the long and silent street, the dawn, with silver sandaled feet, crept like a frightened girl.”

Mohammad Ali Jinnah went to Paris and stood by her side, even eating the same food she was given. Ruttie’s health improved and she moved to Bombay where it took a turn for the worse again. Her loyal friend, Kanji was by her side the night before she died. The last thing she had said to him was, “If I die, look after my cats and don’t give them away.” Ruttie passed away in her sleep on February 20, 1929 — on her 29th birthday.

Jinnah was not a man given to public display of emotion but as Ruttie’s coffin was being lowered into her grave, he broke down and wept without reservation. He had all of her belongings — her clothes, ornaments and pictures packed in boxes and stored away. It is said that he occasionally asked for those boxes be brought to him and would go through her belongings lovingly — then, just as suddenly, he would pack them up again and have them taken away.

It is perhaps, not wrong to say, that the ‘Flower of Bombay’ bloomed forever in his heart.

Newspaper view: [click for larger image]

Soraya Tarzi: a Queen among men

Soraya Tarzi

Soraya Tarzi’s biggest distinction and the impact she had during the time she and her husband, Amanullah Khan, ruled Afghanistan can be judged by the fact that she is the only woman mentioned in the list of rulers of Afghanistan. She was more than just a queen — she was the Minister of Education and actively worked to educate and liberate the women of Afghanistan. She was known just as much for her social activism as she was for her unconventional, and often risqué, style.

Born in Damascus, Syria, on November 24, 1899, Soraya Tarzi was the daughter of a well-known and respected Afghan intellectual and poet, Sardar Mahmud Beg Tarzi. They belonged to the Muhammadzai tribe — a sub tribe of the powerful Barakzai dynasty. As one of Afghanistan’s great thinkers, Mahmud Beg Tarzi was known as the father of Afghan journalism.

His father, Ghulam Muhammad Tarzi, an Agfhan poet and head of the Muhammadzai royal house was exiled in 1881 by Emir Abdur Rahman Khan, then ruler of Afghanistan at the time. Ghulam Muhammad Tarzi and his family moved to Turkey.

In 1901 Emir Abdur Rahman Khan’s son, Emir Habibullah Khan, succeeded him and invited the Tarzi family back to Afghanistan. It was when the Tarzis were received at Habibullah’s court at the royal palace in Kabul that Soraya met the man she was going to marry: Habibullah’s son, Amanullah Khan.

Historians describe Amanullah and Soraya’s relationship as a loving one. They married in 1913 and Soraya was Amanullah’s only wife — something that was previously unheard of. A documentary on the life of the couple described them as “the darlings of Europe in the 1920s — the perfect couple working together to build a new, post-war Afghanistan.”

Amanullah became Emir of Afghanistan in 1919 and king in 1926. Together, along with the guidance of Mahmud Tarzi, they set about trying to modernise Afghanistan. Everywhere Amanullah went, Soraya accompanied him — from cabinet meetings, military parades, visits to conflict zones, etc.

Soraya had been brought up on modern lines by her progressive parents and this background showed up in her lifestyle. She was one of the first women to wear western dress outside of the royal palace in Afghanistan but kept within the bounds of Islam, making sure every part of her body was covered modestly. Initially she also wore a very light veil attached to a flapper hat but when her husband declared at a public event that “Islam did not require women to wear any kind of veil” Soraya, tore off her veil. The wives of the ministers, who were a part of the royal entourage, mimicked her gesture and tore off their veils as well.

Soraya worked actively to liberate the women of Afghanistan, grant them their rights and encouraged them to participate in nation building. She set up the first women’s hospital and girl’s school in Afghanistan. As minister of education, she also arranged to send 18 young women to Turkey to seek higher education in 1928.

King Amanullah and Queen Soraya during their tour in Europe

In one of her more famous speeches she gave at the seventh anniversary of Afghanistan’s independence from the British, she said, “It (independence) belongs to all of us and that is why we celebrate it. Do you think, however, that our nation from the outset needs only men to serve it? Women should also take their part as women did in the early years of our nation and Islam. From their examples we must learn that we must all contribute toward the development of our nation and that this cannot be done without being equipped with knowledge. So we should all attempt to acquire as much knowledge as possible, in order that we may render our services to society in the manner of the women of early Islam.”

Soraya Tarzi also received an honorary degree from Oxford University. King Amanullah was greatly influenced by Mahmud Tarzi who wanted to bring about change to Afghanistan in the form of monogamy, education, employment and no purdah. But the reforms he introduced and the changes he desired were too much too soon. The religious right in Afghanistan were growing increasingly unhappy with his ‘westernised’ administration and the couple’s own relatively liberal lifestyle.

In 1927 and 1928 King Amanullah and Queen Soraya visited Europe where they received a warm reception. They spoke to heads of states, addressed groups of students, were shadowed by the press and so on. But while they were in Europe, trouble was brewing back in Afghanistan. Allegedly photographs of Soraya dining with foreign men and having her hand kissed by foreign leaders, etc., were circulated among the tribal region. This was seen as an affront and outright betrayal of Afghan cultural values and concept of honour. It further fuelled suspicion and discontent among the more conservative parts of the country.

King Amanullah’s reign came to an abrupt end following a rebellion by the conservative Shinwari tribe, led by Habibullah Kalakani, in 1928. They called for the banishment of the royal couple from Afghanistan. King Amanullah abdicated his throne in 1929, leaving his brother Inayatullah Khan in charge as the Emir, to prevent civil war and went into exile to Europe.

Soraya Tarzi spent the rest of her life in Rome, Italy. She passed away on April 20, 1968. Her coffin was escorted by the Italian military before being flown to Afghanistan for a state funeral. She was buried next to Amanullah, who had died eight years earlier, in the family mausoleum in Jalalabad. One of her daughters, Princess India D’Afghanistan, is also an honorary cultural ambassador of Afghanistan to Europe.

In a country dominated by men, where women’s voices are almost never heard, Soraya Tarzi was one woman who left her mark. She was, truly, a queen among men.

Newspaper view: [click to view larger image ]

Jam Nizamuddin II: The Sultan of the Samma dynasty

The tomb of Sultan Jam Nizamuddin, also known as Jam Nindo, is currently undergoing restorative work at Makli - Photo by Madeeha Syed

Driving through the largest necropolis in the world — the historical Makli graveyard in Thatta — is like driving through different eras of ancient history: great kings representing several dynasties are buried here as along with great saints, scholars, philosophers and common men.

As we reached the far end of the Makli graveyard, we found an area that was more restored and preserved than the rest. Men laboured away with machines and tools at a beautiful, intricately carved tomb that was completely different from the others.

This tomb belonged to Jam Nizamuddin II or, as he was popularly known, Jam Nindo — one of the greatest rulers of Sindh and the Sultan of the Samma dynasty.

Jam Nizammudin II reigned from 1461 to 1509 and, along with Sindh, ruled portions of Punjab and Balochistan as well. His rule is known as the golden age of the Samma dynasty as it is during this time that the legacy of the dynasty reached its peak.

He was known for his progressive ideals and his was a peaceful rule. He was a deeply religious man and was known for his pleasant disposition. His kingdom was based on strict Islamic rule where the welfare and safety of all was of paramount concern; travellers could pass through his land without being harmed. After his succession to the throne, he travelled with a large army to Bakkhar, rooting out troublemakers and robbers who had made the life of his people difficult.

Jam Nindo spent much of his time in discourse with learned men of his time. He was known as a seeker of knowledge. It is said that Jalaluddin Rumi sent two of his pupils, Mir Shamsuddin and Mir Muin, to Thatta to arrange for his asylum. When Jam Nindo came to know of this, he sent Rumi’s pupils back with a generous amount of money for travelling expenses and instructed them to return with Rumi immediately. He then ordered spacious, comfortable homes to be prepared for Rumi to live in. Unfortunately, by the time Mir Shamsuddin and Mir Muin reached Persia, Rumi had passed away.

During the latter part of Jam Nindo’s rule, a Mughal army from Kandahar under Shah Beg Arghun tried to invade parts of Jam Nindo’s empire. Under the command of his vizier, Darya Khan, Jam Nindo sent a large army to Halukhar (Duruh-i-Kureeb back then) near Sibi and defeated the army — killing Shah Beg Arghun’s brother, Abu Muhammad Mirza in the fight. The Mughals retreated immediately and they never made another attempt at invasion as long as Jam Nindo ruled the area. Jam Nindo passed away soon after.

The Sindh Samma Welfare Organisation recently paid tribute to Jam Nindo on his 503rd death anniversary last year. Sindh Minister for Culture, Sassui Palijo, announced on the occasion that the Urs of Jam Nindo would be officially organised by the Sindh Culture department this year.

The elaborate and intricate carvings on the tomb of Jam Nindo are symbolic of Hindu architecture in the Gujrati style with a slight influence of Mughal imperial architecture. There is no dome on the tomb; the walls stop at the springing lines — a horizontal line between the springing of the arch. The tomb has been constructed with painstaking detail and is breathtaking to behold.

In contrast, there is a simple, unadorned tomb nearby that the locals say belongs to a pious woman whose prayers protected Thatta from invasion for as long as she was alive and after whom the graveyard was named: Mai Makli.

Behind the tomb you see wide patches of lush green — vegetation that has grown on what once used to be the bed of the River Indus when it still ran through Thatta and when Thatta was a major commercial and cultural hub of the Subcontinent

Newspaper view: [click to view larger image]

Tomb raiders: Guarding the dead

[ See “Ancient art at Chowkandi” a photo essay on the tombs at Chowkandi ]

On the outskirts of Pakistan’s largest city, Karachi, lies a treasure trove for archaeologists and historians alike — the Chowkandi tombs. The tombs at Toti Chowkandi (literal meaning: four corners) were named after Malik Tota Khan, a Kalamati tribal elder who is also buried there. The site predominantly contains tombs that were built for the Jokhio and Baloch tribes between the 15th and the 18th century.

Chowkandi is located 30kms from main Karachi. Once we’re inside, a man with greying hair and a bushy beard, wearing a chequered turban and dhoti walks towards us with the help of his cane. Allah Dina, the caretaker of Chowkandi, has been working here for the past 34 years.

He takes us through each and every tomb, painstakingly pointing out its characteristics while at the same time stressing on the importance of its preservation. “This is our history, this is what we leave behind after we go,” he says. You can tell his attachment to the place runs deep. He even pointed out the curious pattern the ants in the area had traced and the little highways they had built on the rocky terrain of the site.

Allah Dina also keeps an album in which he’s pasted newspaper clippings and photographs sent to him by reporters and visitors (both foreign and local) alike.

While going through the photos in the album, you can see a young Allah Dina smiling back at the camera and how, as the album progressed, he’s aged over time — his warm smile being the one constant feature on his face. The tombs themselves have been intricately carved into unique designs that can also be found on the printed ajraks of Sindh. Each tomb was designed in a way as to provide a clue to the identity of the gender of its occupant — a tiny turban on top of the tomb represented the males whereas the females have jewellery carved on theirs. “Every single grave over here has a unique design,” said Allah Dina, “there are different things carved on each grave — from a sword, turban, jewellery to ajrak patterns — nothing is repeated.” The carvings on the tombs were also very similar to the ones on the graves in Makli, Thatta.

Unfortunately, several months ago, some of the tombs were vandalised by miscreants in an effort to uncover an alleged treasure buried by the Kalamti tribe in their tombs. “A lot of damage has been done. I would have preferred they put a bullet through me instead of harming the tombs,” said Allah Dina sadly, “I spoke to the media. Our directors came to inspect the place. The police don’t know whom to catch. What can they do anyway? It was dark when it happened and this place is open from all sides.”

Restoration work in underway but a trip to the tombs reveals that that is not the only threat to the place: there is no boundary wall keeping potential grave robbers and thieves out. “Anybody can just walk in. This place is very vulnerable to anyone who wishes to harm it,” said Allah Dina.

The approach to the site is littered with trash and squatters increasingly populate the surrounding area. Commercialisation is also increasingly encroaching on the area right outside Chowkandi — not only leading one to miss the location from the main street but also displaying the indifference being shown to an important heritage site. That is a disturbing revelation considering that Chowkandi is an important and established heritage site in Pakistan. While leaving the tombs and the ancient people buried in them, Allah Dina had one last thing to say: “save this place”

Newspaper view: (click for larger image)

Fashionably Lahori

Designer Ammar Belal (R) takes the final walk on the ramp along with his models

Lahore seems almost fashion-obsessed to the non-Lahori eyes. Driving down the main roads and upon entering some of the main commercial areas, one is confronted with a sight not seen very often outside L-city (excluding Lawn season of course): massive billboards advertising local and foreign designer wear. There are also billboards offering the services of numerous fashion photographers while shops stocking designer wear brands dominate almost every other commercial street.

It is safe to say that in this city, where they enjoy sinfully heavy meals such as paiyye and nihari for breakfast, where the glamour of Lollywood and the mystique of the pop-rock industry meet the grace and sophistication of the classical music industry, fashion, style and the art of looking good play a very prominent role in the life of an everyday Lahori.

Lahore is the residing place for large designer brands such as Kamiar Rokni, Hassan Shehryar Yasin, Karma, Libas, Nilofer Shahid, Sara Shahid, Fahad Hussayn and Ammar Belal among others. Prominent menswear designer, Munib Nawaz, has also moved his base from Karachi to Lahore. Even designers from other cities have benefited from Lahore’s drive to make fashion an industry in its own right; it was in Lahore where Karachi-based Nomi Ansari received his degree at the Pakistan Institute of Fashion Design before returning to his native city to launch his brand that would become one of the leading names in the field.

Other than individual designers holding court in their own design studios, there is a multitude of multi-brand designer wear outlets to choose from for fashion-hungry shopaholics. Karachi based multi-brand outfits, Labels and Ensemble have their branches in Lahore as well. Both of the major fashion councils in the country: the Pakistan Fashion Design Council and Fashion Pakistan have a large space for their member designers to stock their collections in — The PFDC Boulevard and Fashion Pakistan Lounge respectively. Lahore’s answer to Armani, Ammar Belal, has extended one of his commercial spaces to other menswear designers who now stock alongside him.

In fact the fashion bug in Lahore is so strong, that it has inspired the food industry in the city as well; one came across the World Fashion Café (near Hussain chowk) — a café that promises to make you look good as well as feed you. The interior of the café is mostly in dark shades of grey and black giving a minimalist look and feel to the place and stocks a collection by a young designer along with a selection of edible goodies. The place is dotted with black and white photographs of prominent individuals in the global fashion industry and the last time I went there, they were playing the Audrey Hepburn classic, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, on one of their large screens.

Giving testimony to how fashion is a prominent part of Lahore is the fact that it recently played host to the third PFDC Sunsilk Fashion Week. Over 30-plus designers came together and showcased collections at the three-day fashion extravaganza which had the likes of Alexandra Senes (French fashion journalist and entrepreneur), Isabelle Ballu (French fashion designer) and Hilary Alexander (renowned British fashion stylist and critic) gracing the event and confirming their commitment to the Pakistani fashion industry. The Pakistani industry might be taking baby steps but it is safe to say that it is slowly and gradually edging its way on to the global fashion map, and so far, Lahore very much seems to be the launching pad for that.